By Mary Cancellieri; December 14, 2020

Every day of this year, whether I have been quarantining or studying or both, I have turned to music to stay positive. Exhibited in news earlier this year, singing together such as on the balconies of Italy or the hospitals in Detroit has made quarantine easier. Music unites us; it reminds us of our common humanity and allows us to be more compassionate to ourselves and others.

Musical performance has been an integral part of humanity as evident by musical instruments dating back to prehistoric times. In 2008, German archeologists excavating sites in Hohle Fels and Vogelherd uncovered a bone flute dating back to the Paleolithic era, over 35,000 years ago. Similarly, a wooden pipe flute from the Early Bronze Age was discovered in Ireland in 2003. Other than flutes, over 122 bronze horns from the Late Bronze Age (which may have sounded like these replica horns) have been recovered in Ireland as well (Colm, 2014).

In more recent history by comparison, music has been crucial for cultures around the world with a variety of instrumentation. For example, Great Plains Native American tribes historically use an assortment of percussion instruments, including drums and possibly rattles, flutes, and whistles, often accompanied by voice (Wishart, 2011). Oceanic ensembles can include percussion like drums and gongs; wind instruments like flutes, panpipes, trumpets, and ocarinas; and other types of instruments such as jaw harps and bullroarers (Kjellgren, 2010). Bullroarers have been used for over 20,000 years, and are most commonly associated with the Aboriginal people of Australia (Australian Bullroarer, 2018). Creating music has been crucial for communities around the world.

Music creates a feeling of “oneness” and “togetherness.” Humans are biologically wired to enjoy the company of others when performing and listening to live music. More specifically, research from a Social and Evolutionary Neuroscience research group from the University of Oxford found that the social bonding effect from music derives from “self-other merging” and the release of endorphins. Self-other merging refers to “when individuals experience their movement simultaneously with another’s” such as when people nod their heads or tap their toes in synch (Tarr et al.). In addition, endorphins are released during “synchronized exertive movements” that would be common with synchronized instrument performance. Endorphins reduce the perception of pain and trigger a positive feeling in the body (Exercise and Depression). This synchronization can influence prosocial behavior– “voluntary actions that are intended to help or benefit another individual or group of individuals” (https://www.learningtogive.org/resources/prosocial-behavior). For example, when caregivers sing to infants while holding them, research published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Science concluded that “moving in time with others– interpersonal synchrony–can direct infants’ social preferences and prosocial behavior” (Cirelli et al.).

Culturally, music is often where people gather together, whether it is in the home or at a concert. Research by the Society for Education, Music, and Psychology and research by the European Society for the Cognitive Science of Music conclude that people like the social connection of experiencing music with other people. Before there were recordings of music, gathering together was necessary to listen to live music. For example, in many communities which pass down information orally, songs have been the way to connect the present with the past and connect the human experience of today with the human experience of past ancestors. For example, in western Sudan, detailed political histories were passed down in epics of warriors and kings in the form of song; these songs are traditionally sung by a class of singers called jeliw (singular: jeli) (Bortolot, 2003). For Great Plains Native Americans, music was integral for when people gather for religious ceremonies, healing, work, games, courtship, storytelling, celebrations, agriculture, and war (Wishart, 2011). Today, Great Plains Native American music is most likely heard in a powwow gathering, but prior to European contact and the forced migration of indigenous people by the Indian Removal Act of 1830, “only a few tribes, namely the Omaha and the Ponca, practiced the communal ritual known today as the powwow” (Suing, 2008). In European history, music was crucial to Christian religious gatherings. For Catholics, Gregorian chants were sung from the tenth century to Mass in the 1950s before falling out of favor (Muth, 2018). After the Protestant Revolution, Lutheran Chorales flourished in the Lutheran church; Martin Luther himself credited music as divine (Protestant Music). In the Baroque Era, composers like Johann Sebastian Bach played in churches before music halls were constructed to better accommodate orchestras in the 1700s (Panagiotopoulos, 2019).

Biologically, self-compassion stimulates the production of oxytocin. The neuropeptide oxytocin is “affiliated with breast-feeding and sexual contact, and is known to play an important role in increasing bonding and trust between people” (Suttie, 2015). According to Dr. Kristin Neff, a major researcher of compassion and self-compassion, “one important way the care-giving system works is by triggering the release of oxytocin” because “increased levels of oxytocin strongly increase feelings of trust, calm, safety, generosity, and connectedness and facilitates the ability to feel warmth and compassion for ourselves” (Neff).

Similarly, music may affect the production of oxytocin. In regard to singing, according to research published in the Journal of Comparative Neurology, “singing” mice with blocked oxytocin receptors vocalized less and did not socialize with other mice when compared to normal mice. This prompted further research for the connection between singing, oxytocin, and socializing. In a human study published in the official journal of the Pavlovian Society, oxytocin levels are significantly raised in both amateur and professional singers when they sing for thirty minutes. In regard to listening to music, a study conducted by the Orebro University Hospital and School of Health, the coronary bypass surgery patients, who listened to ‘soothing’ music (according to the experimenter) for 30 minutes a day after their surgery, experienced higher levels of serum oxytocin than the control group. This research supports the idea the music directly impacts oxytocin levels.

Music lyrics also represent the human condition and thus expands listeners’ empathy. Thupten Jinpa, a former Tibetan monk who is well-known as the English translation for His Holiness the Dalai Lama, describes the human condition as “our experiences of pain and sorrow”– that each of us wishes to be happy and that no one wishes to suffer (Kyte, 2017). This condition has been represented in music since the early days in humanity. For example, the Song of Seikilos (200 BCE), the oldest complete written composition engraved on a tombstone in Turkey (Louderback), is translated as follows:

While you live, shine

Have no grief at all

Life exists only for a short while

And time demands an end.

Aligning with the human condition, this song acknowledges the short nature of human life and warns against grief. More modern examples can include the songs created during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 such as “Six Feet Apart” by country singer Luke Combs, and “Better Days” by the band OneRepublic. Many songs have calming and encouraging moods. One song that particularly highlights the suffering of people during this time would be “Living in a Ghost Town” by The Rolling Stones, a portion of which says:

You can look for me

But I can’t be found

You can search for me

I had to go underground

Life was so beautiful

Then we all got locked down

Feel a like ghost

Living in a ghost town, yeah

Another example is “Grateful” by Jewel. Some of the lyrics include:

When the loudest sound

Is your own life crashing down

And when your friends, when your friends, they don’t come around

There’s one true thing I’ve found

It’s all the little things

Both of these examples put to words the suffering and anxieties faced by people in quarantine, and they were specifically released during this time for that purpose. The action of verbalizing the inner emotions of a group of people (or humanity in general) helps those who are suffering to cope and helps those who are not suffering to empathize.

After great tragedies, music can soothe the suffering and inspire action to help others through radical compassion. After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japanese songwriters used music to recount the tragedy and inspire radical change in nuclear energy. For example, the 1974 ballad “Ippon no Enpitsu” (“One Pencil”) focuses on the final moments of a woman when the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. The lyrics are translated to:

I want you to hear me, I want you to read me

I want you to sing to me, I want you to believe me

If I had a pencil, I’d write my love for you

If I had a pencil, I’d write “I hate war”

I want to give you love. I want to give you dreams

I want to give you the spring. I want to give you the world

If I had a paper, I’d write “I like children”

If I had a paper, I’d write “I want you back”

If I had a pencil, I’d write “the morning of August 6th”

If I had a pencil, I’d write “life of human being”

(Translated by Diazepan Medina, Last edited June 22, 2020)

This song is directly about a tragedy that was a major landmark for the country of Japan because it affected so many people. Therefore, this song is addressed to the people who have suffered, or who know people who have suffered during that time. “One Pencil” uses the mundane activity of writing a letter to a person you love, but then it relates it all of the time and moments lost because of the atomic bombings. This rhetorical strategy heavily appeals to the emotional side of listeners and asks them to place themselves in the life of this woman– to show this woman and, by extension, the people of Japan, understanding and kindness. According to The Japan Times, there was a buffer period of time between the atomic bombings in 1945 and the songs about the bombings (Wong, 2015). After the 1986 Chernobyl and 2011 Fukushima nuclear disasters, songs about the atomic bombings argued against the use of nuclear power. More politically focused songs can include “Flash in Japan” (1987) by Eikichi Yazawa, for example. By advocating for a change in reality for the betterment of others, these activism-related songs are examples of radical compassion.

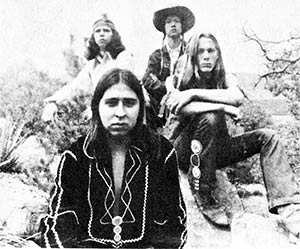

Furthermore, for communities with a history of suffering, contemporary music provides an outlet to express identity, assert values and traditions, and create change. To those unfamiliar with their community, music provides the opportunity to respond with understanding, patience, and kindness, and in times when action is needed, change can occur. For example, Native American contemporary music “critically engage[s] with the stereotypes of Native American cultures and assert[s] their own values and traditions” (Smith & Gist, 2019, 1). The first Indigenous rock band, XIT (pronounced “exit” and referring to the “Crossing of the Tribes”) was formed in 1968 by Rare Earth Records, and their first two albums, The Plight of the Redman (1972) and Silent Warrior (1973), addressed the American Indian Rights Movement by exploring themes of Native American sovereignty and recognition of cultural identity (Smith & Gist, 2019, 14). One more example is Warfield Richards “Buddy” Red Bow, who was a country vocalist and guitarist of Lokota heritage. He used his hit albums, such as Journey to the Spirit World (1983) and Black Hills Dreamer (1991), to promote the Red Power Movement through music (Smith & Gist, 2019, 16). Both of these examples, as artists and activists, used music to promote their identities and movements. They suggested not only an emotional appeal to listeners to understand, but also a call for society to change and show greater kindness and consideration to their communities.

Music has been with humanity since the beginning of human history itself. It has reached every corner of the globe with a variety of instrumentation and it is continuing to evolve. Regardless of the medium, music has the ability to unite people together and inspire a better understanding of suffering and joy.

References

Australian Bullroarer. (2018, July 2). Museum of Anthropology Wake Forest University. https://moa.wfu.edu/2018/07/australian-bullroarer/

Bortolot, A. I. (2003, Oct). Ways of Recording African History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ahis/hd_ahis.htm

Brown, S. C., & Knox, D. (n.d.). Why go to pop concerts? The motivations behind live music attendance. Music. Sci., (21), 233-249. 10.1177/1029864916650719

Burland, K., & Pitts, S. (2014). Coughing and Clapping: Investigating the Audience Experience. New York, NY: Routledge.

Campbell, P., Ophir, A.G. and Phelps, S.M. (2009). Central vasopressin and oxytocin receptor distributions in two species of singing mice. J. Comp. Neurol., (516), 321-333. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.22116

Cirelli, L.K., Trehub, S.E. and Trainor, L.J. (2018). Rhythm and melody as social signals for infants. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci., (1423), 66-72. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13580

Colm. (2014, March 11). Five Ancient Musical Instruments from Ireland. Irish Archeology. http://irisharchaeology.ie/2014/03/five-ancient-musical-instruments-from-ireland/

Exercise and Depression. (n.d.). WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/depression/guide/exercise-depression#1

Fekadu, M. (2020, May 4). 40 songs about the coronavirus pandemic. Listen here. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/2a49e686206f00c6f74d5d132225bc4a

Keating, S. (2020, May 18). The world’s most accessible stress reliever. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200518-why-singing-can-make-you-feel-better-in-lockdown

Kjellgren, E. (2010, Jan). Musical Instruments of Oceania. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/muoc/hd_muoc.htm

Kyte, L. (2017, May 3). Thupten Jinpa, Voice for Compassion. Lion’s Roar. https://www.lionsroar.com/thupten-jinpa-voice-for-compassion/

Louderback, K. (n.d.). Music History: Prehistoric and Ancient Music. A Pianist’s Musings. https://pianistmusings.com/2016/09/30/music-history-prehistoric-and-ancient-music/

Muth, C. (2018, March 7). A brief history of Gregorian chant. America Magazine. americamagazine.org/arts-culture/2018/03/07/brief-history-gregorian-chant

Neff, K. (n.d.). The Chemicals of Care: How Self-Compassion Manifests in Our Bodies. Self-Compassion. https://self-compassion.org/the-chemicals-of-care-how-self-compassion-manifests-in-our-bodies/

Panagiotopoulos, V. (2019, April 16). The History and Future of Live Music. The Asian Entrepreneur. https://www.asianentrepreneur.org/the-history-and-future-of-live-music/

Protestant Music. (n.d.). Musée virtuel du protestantisme. museeprotestant.org/en/notice/protestant-music/

Smith, S., & Gist, B. (2019). Native American Audio Project Research Guide. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/rr/record/NativeAmericanAudioLC.pdf

Suing, M. (2008, July). Great Plains Indians Musical Instruments. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plai/hd_plai.htm

Suttie, J. (2015, Jan 15). Four Ways Music Strengthens Social Bonds. Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/four_ways_music_strengthens_social_bonds

Tarr, B., Launay, J., & Dunbar, R. (n.d.). Music and social bonding: “self-other” merging and neurohormonal mechanisms. Front. Psychol. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01096

Universitaet Tuebingen. (2009, June 25). Paleolithic Bone Flute Discovered: Earliest Musical Tradition Documented In Southwestern Germany. Science Daily. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/06/090624213346.htm

Wishart, D. J. (2011). Native American Music. Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.mus.034

Wong, D. (2015, Aug 9). The song that dealt with the atomic bombs. The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2015/08/09/music/song-dealt-atomic-bombs/